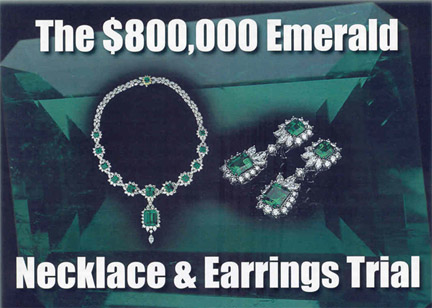

The $800,000 Emerald Necklace & Earrings Trial

In what could have been the next “Fred Ward” emerald trial, the jeweler in this case prevailed. It was not that he was without error. However, had he lost this trial, it would have wrongly cost him his business, and could have had a severe long-term affect on the emerald industry. In the end we believe justice prevailed but not without some cost, and hard lessons have been learned.

By Richard B. Drucker, GG & Stuart M. Robertson, GG

Download this article in PDF

Background

Robinson Brown, Jr., then chairman of the Brown-Forman Co.(distillers and distributors of several brand name liquors), asked his longtime jeweler James Jackson (Aesthetics in Jewelry) to find for him an exquisite necklace and earrings similar to that which Richard Burton once gave to Elizabeth Taylor. He was willing to spend a substantial amount of money, well over a million dollars if necessary. Jackson states that Brown had explained that he wanted to dedicate the emerald jewelry to his late wife’s memory by naming it after her and eventually donate it to a local museum. Although his heirs dispute Jackson’s assertion that their father intended to donate it, there are three interesting facts that appear to support Jackson’s statement: 1) Brown’s wife was deceased at the time he commissioned Jackson to produce the jewelry. 2) Brown had updated his will shortly before his death but did not bequeath the jewelry to any of his three daughters, two daughters-in-law, sons, or anyone else. 3) Brown had reportedly commissioned a presentation box with engraved plaque for the piece.

The search for the special suite of emeralds led Jackson to Ray Zajicek, president Equatorian Imports, a prominent emerald dealer. Zajicek told Jackson that he knew of a suite of fine Colombian emeralds already mounted in a necklace and earrings that he believed Jackson should see. Zajicek was familiar with the suite because he had been commissioned by well-known gem dealer Richard Krementz to travel to Colombia to acquire the fine emeralds comprising the suite. They assembled the necklace over a period of more than two years and required several trips to Colombia to complete. It contained 13 matched emeralds, all from the Chivor mine, the largest being 18.47 carats. Like all emeralds that Zajicek now deals in, these stones were sent to the Clarity Enhancement Laboratory in New York, Arthur Groom and Fernando Garzon, partners. In their process, any previous enhancement is removed and then re-treated using the proprietary enhancement, ExCel™.

Platinum was used to make the exquisite hand crafted necklace. The necklace contained 42.99 carats of emeralds, 34.98 carats of white diamonds, and .51 carat of yellow diamonds. The earrings contained 11.55 carats of emeralds and 6.98 carats of diamonds. The necklace was important enough to have caught the attention of an actress, who chose to wear it to the Golden Globe Awards.

Jackson acquired the jewelry for the wholesale price of $500,000. In February 2005, Jackson showed the necklace and earring set to Brown who agreed to purchase it for $800,000 plus sales tax. As the purchaser and rightful owner, Brown named the necklace “The Queen of the Creek,” a nickname he called his wife. Unfortunately, Brown died just five months later on July 28, 2005.

Brown’s heirs were now in possession of the necklace and earrings. The co-executors of the estate were Mr. Brown’s two sons. They apparently decided to convert the emerald set to cash for distribution in the estate. According to the complaint filed with the court, the heirs attempted to sell the necklace, at which time they were led to believe that the gems were not well-matched nor were all the stones “fine” quality. Interestingly, in February 2006, a relative of the Browns obtained an “Insurance Replacement” appraisal from Vartanian & Sons in New York for $200,000 and one from Bradley Lampert of New York for $180,000 stating it to be a “Retail Value.” Despite the considerable number of stones comprising this suite, these two appraisals contained identical descriptions and weights and similar “retail values” that are less than half of the wholesale price charged by the reputable emerald dealer only one year earlier.

Citing these appraisals, the Browns now felt that they had been deceived so they went to Jackson and asked for a full refund including the sales tax paid. Jackson declined but did offer to take the items on consignment and look for another buyer. The heirs agreed to this but after two months they took the necklace back. They went to New York and visited both Sotheby’s and Christies. In April 2006, auction estimates were obtained from Christie’s and Sotheby’s for $150,000-$200,000. Auction estimates tend to be attractive enough to entice potential buyers to bid on the lots. However, under the circumstances of this case they would not be indicative of a retail replacement value. They went to another “buyer” of jewelry on 47th Street and received a similar cash offer.

In June 2006, the Browns filed suit in Louisville, Kentucky. The initial Complaint consisted of nine counts, summarized here. I. Fraud and misrepresentation. II. Negligence. III. Breach of agreement. IV. Jackson should rescind $848,000. V. Deceptive acts misrepresenting value and quality, therefore entitled to compensatory damages, punitive damages, and attorney fees. Jackson’s attorney Sandra McLaughlin believed the case to be a stretch at best and questioned whether it would proceed.

Then, in November 2008, the emerald set was submitted to the American Gemological Laboratories (AGL) for Colored Stone Origin Reports. In part, the reports state that in the opinion of the lab, the origin [of the emeralds] is Colombian. The reports indicate that the stones show evidence of an insignificant to faint or faint to moderate degrees of enhancement. The enhancement is classified as an “Organic Polymer Type.” It does not identify the brand of filler as ExCel™, though they have issued other reports that identify this brand of filler.

In December, the Browns amended their complaint to further charge that, “In selling the jewelry to Plaintiff, Jackson failed to disclose that the emeralds in the necklace and earrings had been treated with a non-traditional polymer

enhancement, and that as a result, the salability and/or marketability of the jewelry had been greatly reduced.” The

added counts are summarized here. VI. Brown relied on a written appraisal by Jackson for $960,000 wholesale to decide

on purchase. VII. Jackson represented the retail value to be $1.2 million. VIII. Jackson failed to disclose a nontraditional

polymer enhancement greatly reducing salability and marketability of jewelry. IX. Concealment of material information.

And so the trial begins…

The Plaintiff’s Testimony

A friend and colleague, Barry Block had been approached long before the trial to evaluate the emerald necklace and earrings. At that time, he was unaware of the particular details of the dispute and was simply asked to render an opinion of the replacement value. According to Block, the attorney for the plaintiff did not ask for a written report. At the trial, Block verbally offered a retail range of $600,000 using a cost approach to value and being aware of the wholesale cost that Jackson had paid. He used a markup that he thought was reasonable based on conversations with other jewelers in the competitive New York market. While one might disagree with this approach, remember that Block was not provided information that the jewelry was subject to litigation and initially rendered a verbal opinion of replacement value. He never formally valued the item, nor prepared a report based on comparables or with consideration of other factors related to the case. In his testimony, Block also addressed the lack of a cohesive position regarding the quantification of enhancement on the value of emeralds as an industry practice.

The main witness for the plaintiff was Cap Beesley, president of the AGL at the time the reports were made but currently no longer associated with that laboratory. Mr. Beesley’s testimony was reportedly based on the premise that these emeralds were treated with a non-traditional enhancement and not cedarwood oil, therefore their value and salability was diminished. The line of reasoning paralleled that used in the Fred Ward emerald case adjudicated more than a decade earlier. The testimony discussed the perception that polymers improve the appearance of low quality emeralds to such an extent as to be deceptive. It was also stated that the market traditionally has accepted cedarwood oil, while polymer treatments “devalue” stones. Jackson’s attorney successfully redirected the testimony away from the discussion of unrelated events from the mid-1990s to the facts relevant to the current period.

Under cross-examination, Beesley explained to McLaughlin that enhancement quantification was not an issue of volume or the amount of filler placed in the stone but was instead an issue of visual impact. That had been one of the authors (Robertson) understanding as well. As Robertson would later point out in testimony, the fact that the stones in the Brown necklace and earrings had been graded by Beesley as having an insignificant to faint level of enhancement contradicted the position that these emeralds would have changed significantly in their appearance as result of polymer enhancement. The obvious problem the plaintiffs were faced with was that Beesley himself had examined and quantified the amount of filler in the emeralds at the center of this case. Furthermore, these were treated with the proprietary ExCel™ process and not any of the less stable polymers in use in the 1990s. In reality, the emeralds at the center of this case are fine gem quality Chivor emeralds and would be regardless of whether treated with ExCel™ or cedarwood oil. Under further cross-examination, Beesley did acknowledge that emeralds with the range of enhancement assigned to these stones are rare. She then presented a document from the Eternity Emerald website containing a quote from Beesley in support of ExCel™ stability. He has stated it to be superior to oil as a treatment. Beesley also collaborated with Groom in the design of the exclusive emerald reports produced by his lab at the time, to help Groom effectively market this treatment.

The Defense

It is important to understand that ExCel™ evolved from the enhancement debate that took place during the 1990s and gained greater attention following the verdict in the Ward trial. However, much has occurred in the way of education and research since that period more than a decade ago. Any comparison even by inference of ExCel™ to less stable fillers like opticon, is misleading. Furthermore, ExCel™ comes with a lifetime guarantee and Clarity Enhancement Laboratory will remove the ExCel™ and re-treat with any treatment of choice for the client including cedarwood oil.

Stuart Robertson was called as an expert witness by the defense in this case. Specifically, he was identified as an expert in treatments and their effect on gemstone pricing. Robertson explained that emeralds are enhanced to replace the air in surface reaching fissures with a substance with an RI closer to that of emerald. There can be a significant change in appearance between a fissure filled with air and one filled with a medium like ExCel™ or cedarwood oil. However, we would not expect to see a significantly different appearance in a fissure filled with oil and the same fissure filled with ExCel™. It is expected that there would be a difference because the two mediums are different. The ExCel™ has an RI within the range of emerald so it will mask fissures more effectively. However, it is not expected that the visual impact would be significant such as in converting commercial quality emerald to fine quality. He also explained to the jury the differences in various emerald treatments and how enhancements affect pricing.

The main premise of his testimony was that enhancement is an accepted practice in the emerald industry, that there are several mediums associated with this practice, and that the medium involved in this case is a stable, colorless enhancement accepted in the trade. From the questioning at both his deposition and in court, it became apparent that the plaintiff’s counsel believed that the issue in the 1997 Ward case concerned the use of undisclosed polymer in the enhancement process. That is a questionable interpretation as the issue was one of undisclosed enhancement, not necessarily a polymer enhancement. In Robertson’s opinion, the Ward case really had little relevance to the Browns’ case. Again, the industry has evolved in the more than a decade after the Ward case and the market has a better understanding of the different mediums commonly used in emerald enhancement. Much of Robertson’s testimony involved differentiating the proprietary enhancement ExCel™ from less stable treatments like cedarwood oil or opticon, identified in the earlier Ward case.

As the market evolved, the trade gained a greater acceptance of the premise that emeralds are enhanced and have been for two thousand years. It is not surprising that segments of the trade are embracing stable, colorless medium with superior properties compared to some treatments used more commonly in the past. The issue is choice—a point the jury seemed to grasp.

Richard Drucker also testified for the defense. He was asked if he had ever seen the necklace previous to his court appearance. The plaintiffs had refused to make the necklace available for a formal viewing and report; therefore, he only viewed photographs and the AGL reports and could not formalize an appraisal value. In court, he was shown the necklace and earrings and the overall quality was easy to identify as being in the extra fine category. The attorney then gave copies of the GemGuide emerald pricing page and reconciliation page for treatments to the jury to follow along. We discussed these and then McLaughlin went to the easel and started listing each of the major emeralds, asking Drucker to offer a verbal opinion of value. Understanding that this was not a formal appraisal, previous experts on both sides had agreed that these were high quality so the exercise used a justifiable low end of extra fine to begin. He also explained that a premium might be justified for the level of treatment as shown on the reconciliation page from the GemGuide. Without any premiums for factors like matching, provenance, enhancement level, etc., after only a few of the major emeralds were valued, we were above the value of the original complaint claiming worth of only $150,000 to $200,000.

The Verdict

When the trial ended after six long days of testimony, the jury went into deliberation. Being that this was a civil trial, the 12 jurors did not need to reach a unanimous decision, only a majority decision. They deliberated for less than an hour, took their vote, and returned the verdict. The vote was 12-0 in favor of the defendant, James Jackson, Aesthetics in Jewelry.

The Truth Regarding Emerald Treatments

The market has been experiencing a period of evolution during the past decade regarding the acceptability of enhancement mediums. The notion that polymers “devalue” emeralds defies logic. A knowledgeable emerald expert like Ray Zajicek would not buy a suite of gem quality Chivor emeralds and then treat them with ExCel™ to make them less valuable and saleable than if treated with cedarwood. The market has a choice and therefore we observe preferences among market participants as a result. Buyers respond based on those preferences. What we do not see is a trend to suggest that people will buy a polymer treated emerald because “it is less” or an oiled stone because “it is more.” A price relationship based on this scenario has not been observed in the market.

During the past decade, several important studies have been conducted on various aspects of emerald enhancements, including the contributions of Dr. Mary Johnson for Gems & Gemology (Summer 1999 and Summer 2007). As a result, market participants have acquired a greater understanding of the history of the practice and issues of stability, etc. As the market learned the history of the process better, and could separate fact from fiction, participants began to address enhancement from a position of personal preference. In essence, buyers and sellers have choices. The stigma associated with certain polymers resulted from their lack of long-term stability. ExCel™, specifically formulated for clarity enhancing emeralds, is gaining wider market acceptance.

Some market participants prefer cedarwood oil, others polymers, and still others paraffin. The country of origin of the emerald and location of cutting center in which it is processed both influence the choice of enhancement medium. The notion that the international gem community embraces cedarwood oil exclusively, is not supported in reality. Instead, what the market appears to wants is a medium that is 1) colorless and therefore will not influence the natural color of the emerald 2) stable and will not dry out or fade with time and 3) can be cleaned out should the ultimate consumer prefer to have their emerald enhanced with a different medium.

In testimony, Robertson pointed out that although cedarwood oil has been referred to as “natural,” in fact no enhancement medium occurs naturally in an emerald. In other words, someone needs to place the filler into the stone. That being the case, a more stable enhancement may be more desirable in protecting the long-term beauty of the gem.

What Could Have Been a Disaster

Had this case prevailed for the plaintiffs, this could have had a huge negative impact on the jewelry industry. Of considerable concern is that a precedent might have been set that the inheritors of jewelry had the right to a refund simply because they did not want the jewelry. Remember, the initial complaint was not about treatments at all. In our opinion, plaintiffs were seeking a position from which they could force Jackson to refund the money. They were upset when Jackson would not take the jewelry back. The lawsuit only began when they first went to New York and were falsely led to believe that the jewelry was worth considerably less than the retail price paid. Later, the issue of treatment took center stage.

Had the plaintiffs prevailed, this had the makings again of being the next Fred Ward emerald case. While other factors also contributed to the decline in the emerald trade and emerald prices, that single trial impacted confidence in the industry for several years in the 1990s. Raising awareness of treatments is a positive from these cases, and certainly we would never condone hiding a material fact that negatively affects value, but challenging the practices of an entire industry over a false claim is not considered justice.

Hard Lessons

At the trial, Jackson’s appraisal was blown up to large poster size and labeled as one of plaintiff ’s exhibits. Experts, including Drucker, were asked about the appraisal. Jackson was chastised for his use of the word wholesale instead of retail. He was confronted for appraising the necklace for $960,000, when he sold it for $848,000 with tax. The report was criticized for the lack of any treatment information. As experts, it is not our role to advocate for any position other than what we believe to be the truth. Drucker agreed that the report lacked the desirable degree of treatment disclosure especially considering that the jeweler knew from the Equatorian Imports memo that the stones were treated and he stated to have disclosed this verbally during the sale.

Jewelers must understand that unless there are special circumstances, the appraised value should be the selling price. Whatever your margins, it is still retail to the consumer. Sales to end users are by definition “retail” not wholesale and should be labeled as such. As for treatments, although the FTC guidelines are not entirely clear on how disclosure should take place, written is always the safe bet. Verbal disclosure is still disclosure but difficult to support. It should be on the sales receipt and on the appraisal. Even though Jackson’s appraisal did not influence the sale, it could have cost him his business and life savings. A verdict for the plaintiff could have been for damages, attorney fees, and the refund of the purchase price plus his own legal fees. In total, this could have approached $2 million.

This unfortunate case provides a lesson for members of our industry, not the least of which is that treatment disclosure should be in writing. And for appraisers, treat every assignment whether written or verbal as if you will be called on to defend it in court. And if you are asked to defend it, of course you must tell the truth and your testimony should be the same regardless of which side hires you.

Colorless enhancements such as cedarwood oil or the polymer Excel™ do not alter the color of the emerald but are intended to mask the visual appearance of fissures within the stone. This before and after image is an example of this but does not necessarily reflect the emeralds in this case. They only provide an example of the benefits of treatments in emeralds. Courtesy of Clarity Enhancement Laboratory.

As featured in JCK magazine:

ExCel Enhanced Emeralds ExCel at Christie's

A pair of emerald earrings with six round brilliant-cut emeralds (t.w.

93.96cts.) recently sold at

Christie's

Auction for $410,700.

Significantly, they were accompanied by an

American Gemological

Laboratory (AGL) report stating that the Colombian emeralds had been

enhanced by the organic polymer ExCel.

Arthur Groom, a retail jeweler and emerald wholesaler whose company co-developed the ExCel enhancement, believes the sale might signify the turning point at which the industry finally accepts ExCel as a legitimate treatment.

Fernando Garzon of the Clarity Enhancement Laboratory (CEL) in New York,

Groom's partner and the developer of the ExCel enhancement process,

says, "The biggest hurdle is the word "polymer." It's usually the kiss

of death."

He believes ExCel's lifetime guarantee was the reason the earrings made

a positive showing at the auction.

A MAGNIFICENT PAIR OF EMERALD AND DIAMOND EAR PENDANTS

445

Each circular-cut diamond surmount, suspending a graduated series of

circular-cut emeralds, spaced by circular and square-cut diamond links,

terminating in a calibre-cut diamond drop, mounted in platinum.

With report 0303085 dated 2 April 2003 from the

Gueblin

Gemmological

Laboratory stating that the six faceted gemstones (tested insofar as

mounting permits) are natural emeralds. Gemological testing revealed

characteristics consistent with those of emeralds originating from

Colombia and show indications of minor clarity enhancement.

With reports CS35187, CS35188 and CS35189 dated 19 November 2001 from

the American

Gemological Laboratories stating that based on available

gemological information, it is the opinion of the Laboratory that the

origin of the emeralds weighing approximately 8.10, 9.32, 9.74, 9.81,

12.85 and 14.14 carats would be classified as Colombia. Clarity

Enhancement: Faint and Faint-Moderate (Organic: polymer Type: ExCel

Process)

The total weight of the emeralds is approximately 63.90 carats

Estimate: $400,000-500,000